The Immorality of Modern Polygamy

The fine line between justice and justification: Why permissibility doesn't mean practicality.

A woman exhibits an immense amount of emotional turmoil and pain over the sexual sin of men throughout history. Even today, she watches the proliferation of anti-women rhetoric online, and men who share these sentiments collect into red-pill subcultures dedicated to praising concepts such as the feminine imperative, male dominance, polyamory, or infidelity. Seeking consolation, she turns to religious scripture, only to read the words “…then marry other women of your choice—two, three, or four” [An-Nisa, 4:3]. Are women truly secondary extensions of men? Is her purpose to sexually serve and satisfy men? Is her husband inherently disloyal?

No.

The practice and concept of polygamy within the scope of Islam is often misrepresented, misunderstood, and weaponized. I have grappled with this topic for a long time, and often found myself consumed with trying to navigate the purpose and morality of it. After two years of researching and engaging with the topic of polygamy, I have concluded one thing: Polygamy is practical, not ideal. This premise will serve as the foundation of my argument throughout this article. My motivations in writing this are not to denounce the institution, but to clarify its purpose, hold men accountable, and expose the ways in which it is misused.

Section 1: History and Science of Polygamy

This section will address any background information regarding the origin and science of polygamy. It will function against the argument that men are inherently more sexual (a topic I will cover in another article) and polygamous.

1.1 Prehistoric Humans and Evolution

The concept of mating with multiple partners predates recorded history, with many primitive societies relying on this sexual dynamic for survival. The idea that humans have always been monogamous, especially women, is a conventional wisdom that contradicts anthropology and evolutionary biology.

The Mating Mind is a book written by Geoffrey Miller, exploring the influence of sexual selection on modern human characteristics and development. Miller visits a plethora of theories regarding sexual behavior between men, women, and animals. Most notable, though, is his discussion of monogamous and polygamous behaviors in primates. He argues that the distribution of food in a particular environment influences the distribution of females, which influences the distribution of males, and thus determines the sexual habits of a population. When food is ample, females band together and share resources. A single male can ‘claim’ this band of females, limiting sexual access from other males, resulting in a “harem system of single-male polygyny” (Miller 183). However, when food is scarce, females rely on each other for resources and their distribution becomes too large for a single male to limit their sexual access. Instead, a complex multi-male and multi-female group forms, with respective coalitions.

This is where sperm production comes into play. The idea that sperm competition played a significant role in penile length and testicle size is a prominent and substantiated theory in evolutionary biology. Larger evolved testicles allowed for “copious ejaculates” and “high sperm counts”, and longer penile length provided an advantage for depositing semen closer to the female cervix (Miller 183). Polygamous harem groups are a common mating structure amongst gorillas. Because a single male limits sexual access from other males, there is a lack of sperm competition, so gorillas possess much smaller testicles and shorter penile lengths. On the other hand, chimpanzees often exhibited polygamous mating dynamics, resulting in increased sperm competition. Female chimpanzees would select the best sperm by mating promiscuously. Chimpanzees are our closest living relative, possessing penile lengths of approximately 14-17 cm while erect (Dixson). Whereas gorillas, who are less related to humans, have significantly smaller penises that are less than 6 cm while erect. Human penile length and testicle size is comparable to that of chimpanzees and bonobos, who also exhibited promiscuous and matriarchal mating habits.

Furthermore, William Eberhard’s Sexual Selection and Animal Genitalia presents similar information. He discusses how significant modification of male genitalia occurs when species split. This is due to female preference, which focuses on penis form details and encourages micro-innovations, thus generating sexual ornaments or genitals that operate as isolators. Eberhard argues convincingly that male genitals in a wide range of species are shaped as much by female choice as by the demands of sperm delivery.

For these reasons, Geoffrey Miller, William Eberhard, Hugh Paterson, and many other evolutionary biologists have theorized that our hominid ancestors likely exhibited similar sexual dynamics. Or in other words, male and female prehistoric humans both exhibited non-monogamous mating structures. I present this information, and will continue to do so, with the purpose of dispelling any unscientific or preconceived claims that men or women are inherently polygamous. Such sexual behavior is largely influenced by environmental stresses and resources.

1.2 Ancient and Modern Dynamics

So, where does monogamy, marriage, and religion fit into this? The marital institution is believed to date as far back as hunter-gatherer periods, likely beginning as informal pair-bonding for reproductive success and survival. Male-male competition within polygamous societies likely resulted in social instability and violence. Ancient humans may have shifted to monogamous structures as it reduced conflict, thereby increasing group cooperation and social stability. Additionally, in monogamous relationship structures, males were certain of paternity, making them more likely to invest in the success of their offspring. This produced better-nourished and healthier offspring, consequently improving reproductive success. However, the shift towards monogamy was not strictly about reproductive success and improving offspring survival, it was also about social order and stable-inheritance.

We observe the first formal establishment of marital institutions in ancient Mesopotamia, with recorded marital laws appearing in the Code of Ur-Nammu and the Code of Hammurabi. As time progressed, more societies began implementing legal and contractual marriages. Whether they practiced strictly monogamy or polygamy varied among societies. Ancient Egyptians were largely monogamous, but elites such as Cleopatra or Tutankhamun engaged in more promiscuous and polygamous behaviors. On the other end of the spectrum, polygamy and concubinage was common amongst the ancient Chinese elites and noblemen. Marital fidelity largely depended on respective sociocultural values, but with the introduction of various abrahamic religions, these dynamics became more clearly defined. Islam permitted up to four wives and concubinage. Early Christians discouraged polygamy, though the Old Testament contains numerous accounts of Jewish and Christian historical figures engaging in polygamous behaviors.

1.3 Neurobiology and Endocrinology

Whenever individuals claim that men have an inherent inclination towards polygamy, I typically ask them to cite which brain region or hormone is directly responsible… because there isn’t one.

However, there are a plethora of hormones specifically associated with fidelity. First is oxytocin, often referred to as the “love” hormone. It’s not actually responsible for romantic feelings or love, but it is responsible for pair-bonding and monogamous behaviors. Pair-bonding is the formation of long-term deep emotional and physical relationships. The reason mothers have a biological instinct to protect and nurture their children is because an influx of oxytocin is released during childbirth and breast-feeding. Another example is in romantic relationships, where oxytocin is released during physical touch, sexual intimacy, or orgasm. It bonds us to individuals and reinforces emotional attachments. Males and females in committed relationships typically have higher levels of oxytocin, promoting fidelity and monogamy.

Another hormone is vasopressin, also known as the ‘mate-guarding’ hormone. Jennifer L. Garrison et al. identified vasopressin as a modulator that increased the “coherence of mating behavior” in male roundworms (Garrison et al.). Mutant males that lacked the peptide nematocin or its receptors exhibited dysfunctional and impaired mating habits. They exhibited “fragmented mating motor patterns”, difficulty locating the vulva, and inefficient sperm transfer. This study reinforces vasopressin’s fundamental role in executing reproductive behavior. In terms of monogamy, studies were conducted on prairie voles and meadow voles by Carter et al. and Young et al. Carter and Young both investigated the influence of oxytocin and vasopressin on sexual behavior in prairie voles (a monogamous species known for strong pair-bonds) and meadow voles (a polygamous species). In both studies, they found that prairie voles had higher levels of vasopressin and oxytocin. When the receptors for these hormones were blocked, prairie voles were incapable of forming strong pair-bonds. Meadow voles contrastingly possessed fewer receptors for these respective hormones. All three studies suggest vasopressin and oxytocin play a role in maintaining fidelous relationships.

[Some may argue that hormones such as testosterone or dopamine may promote promiscuous or novelty-seeking behaviors, thus resulting in polygamous tendencies. Though I would strongly contend with this as there is no substantive evidence that these hormones directly influence a sexual preference for polygamy.]

Both of these crucial hormones are strongly involved with the Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA) of the brain, which functions as an extension of our reward system. It is an evolved brain region and can be used to argue there is an inclination towards monogamous behavior in humans. The VTA is less developed in some species, typically only functioning to support basic survival traits. For example, Lizards have a less developed VTA and also have a male dominated polygamous mating structure. Meadow voles, as mentioned previously, are polygamous and have decreased activity in the VTA. On the other hand, mammals such as wolves and birds are monogamous species, with a significantly more developed and active VTA. Sarah Alger et al. conducted an in depth study of neurogenetic mechanisms and pair-bonding in zebra finches, highlighting the role of dopamine and neuromodulators in maintaining monogamous relationships. They specifically found that female partner behaviors shaped the molecular and genetic organization of the VTA, influencing pair-bonding and promoting life-long monogamy (Alger et al.).

[To clarify, I am not arguing that a larger VTA makes a species inherently monogamous. I am merely positing that it promotes an inclination towards monogamous behavior, but deviations certainly exist.]

Edit (05/07/2025): Wanted to add an additional correlative study from Walum et al. (2008, PNAS), which found that men who possessed an allele variant of AVPR1A called the 334 allele had lower pair bonding scores, increased relationship trouble, and lower relationship satisfaction. This gene was statistically linked to reduced pair-bonding behavior and relationship quality due to having fewer or dysfunctional vasopressin receptors. Thus, this affects their capacity to empathize, emotionally bond, or engage in committed behaviors. As noted previously, lower levels of vasopressin in males typically results in impaired mating functions, so it’s not necessarily a good thing. Healthy human males generally should have functionally adequate levels of vasopressin and receptors.

Section 2: Islamic Definition and Understanding

Polygamy is a practice in Islam that allows a man to marry up to four women simultaneously, provided he can fulfill obligations of fairness and justice. It is permissible, not obligatory.

2.1 Purpose

The primary purpose and function of polygamy is not objectively cited in any religious scripture such as the Quran, ahadith, or the seerah. However, there are a plethora of speculated reasons for this ruling. A strong argument is that it was revealed for the purpose of social welfare, i.e., providing widows, orphans, previous slaves, prostitutes, and unmarried women with support and sustenance. This was particularly important in early Islamic society where women outnumbered men due to war, conflict, and other casualties. Since women during this time period typically did not have the opportunity to pursue an education or financial independence, they would resort to prostitution to make ends meet. Or in other cases, women would be captured in war and sold as slaves. Polygamy would ensure the care of women who are otherwise left without protection and support. This is observed through the Prophet Muhammad’s (ﷺ) marriages, in which nearly all of his wives were widowed, divorced, or previous slaves.

Another argument for polygamy is reproduction and lineage. Increasing the size of the Ummah was something the Prophet (ﷺ) strongley proponed. Marrying multiple women provided the opportunity to produce as many legitimate children as possible while simultaneously preserving lineage.

A common argument I frequently come across is that polygamy was permitted to satisfy men’s lustful appetite and prevent them from committing adultery. This argument is incredibly flawed as it positions polygamy as a function for the desire of men, and not for the sustenance and protection of women. I do not believe such a hubris and revolting sentiment is consistent with the values that Islam maintains. I also believe it opens the ground for justifying infidelous tendencies, which I will address later.

The wisdom of the Prophet’s (ﷺ) marriages is incredibly important to understanding the manner in which polygamy was implemented and practiced. The Prophet (ﷺ) did not marry multiple women to satisfy his hubris lustful desires, and attempting to attribute such a characteristic to him is inappropriate and arguably profane. He married women for political alliances, strategic reasons, or to provide them with support and welfare. He married older women (e.g., Khadijah and Sawdah) in a society where women beyond their twenties were considered to be spinsters. He married divorced women (e.g., Umm Salama, Zaynab) despite society writing these women off as “used.” His marriage to Aisha (RA) was the only exception in terms of youth, but she was also the most knowledgeable. Contemporary implementations of polygamous practices often overlook this wisdom and focus on marrying younger, prettier women out of lust and desire. If you poll a majority of men and ask them whether they would prefer to marry a young, beautiful, virgin woman or a widowed/divorced woman with children who is in need of financial support, most would likely choose the former, despite the immense reward in choosing the latter. The way polygamy is positioned today–often motivated by personal desire rather than responsibility, care, and justice–deviates from its clear intended purpose in Islam.

2.2 Conditions

An overarching condition of polygamy is justice and fairness in terms of financial investments, clothing, spending the night with them, etc. See the following references:

“…but if you fear that you shall not be able to deal justly (with them), then [marry] only one.” [al-Nisa 4:3]

“You will never be able to do perfect justice between wives even if it is your ardent desire.” [al-Nisa 4:129]

“Yet, men are prohibited from marrying more than four wives, as the Ayah decrees, since the Ayah specifies what men are allowed of wives, as Ibn `Abbas and the majority of scholars stated.”

“Marrying Only One Wife When One Fears He Might not Do Justice to His Wives Allah's statement…The Ayah commands, if you fear that you will not be able to do justice between your wives by marrying more than one, then marry only one wife, or satisfy yourself with only female captives.” [Tafsir Ibn Kathir]

Ibn Kathir’s Tafsir covers the importance of equality and how this is a right of the wives. And if men cannot fulfill this right, they should limit themselves to one wife or a “female captive.” To clarify the point on concubinage, the Prophet (ﷺ) emphasized marrying slaves or freeing them, not keeping them.

You must treat each wife equally in terms of material and sexual needs. For example, the Prophet (ﷺ) would spend time equally with each of his wives, and would essentially have ‘sexual rotations’, i.e., he would ensure he has been intimate with each of his wives before he had intercourse with the first again.

"The Prophet (peace be upon him) used to divide his time equally among his wives and would say, 'O Allah, this is my division in what I can control, so do not hold me accountable for what You control and I cannot control.” Sahih al-Bukhari (5214)

"The Prophet (peace be upon him) would stay with each of his wives for a day and a night, except for Sawdah bint Zam'ah, who gave her day to Aisha (may Allah be pleased with them)." Sahih Muslim (1463)

"The Prophet (peace be upon him) used to visit all his wives in one night, and he had nine wives at that time." Sunan Abu Dawood (2131)

For those who lack the resources and finances to be able to sustain multiple wives, let alone one wife, they are encouraged to fast to modulate their desires.

“And let those who find not the financial means for marriage keep themselves chaste, until Allah enriches them of His Bounty.” [al-Nur 24:33]

“O young men, whoever among you can afford marriage, let him marry, for it is more effective in lowering the gaze and guarding chastity. Whoever is not able to marry, let him fast, for it will be a shield for him as fasting diminishes his sexual desire..” Sahih al-Bukhari (5065), Sahih Muslim (1400)

These references refute the argument that polygamy exists to satisfy male desires, rather, it reinforces the sentiment that it exists for the benefit of Muslim women. While marrying for sexual desires is not inherently haram, because the man’s intentions are misplaced, it opens the door for injustice to occur. The Prophet (ﷺ) strongly warns against unjust polygamy…

“The Prophet (ﷺ) warned: ‘When a man has two wives and does not deal justly between them, he will come on the Day of Judgment with one of his sides leaning (paralysed)’.” (Sunan Abu Dawood 2133, Tirmidhi 1141)

Section 3: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs & Alderfer’s ERG Theory

3.1 Understanding Maslow’s Theory

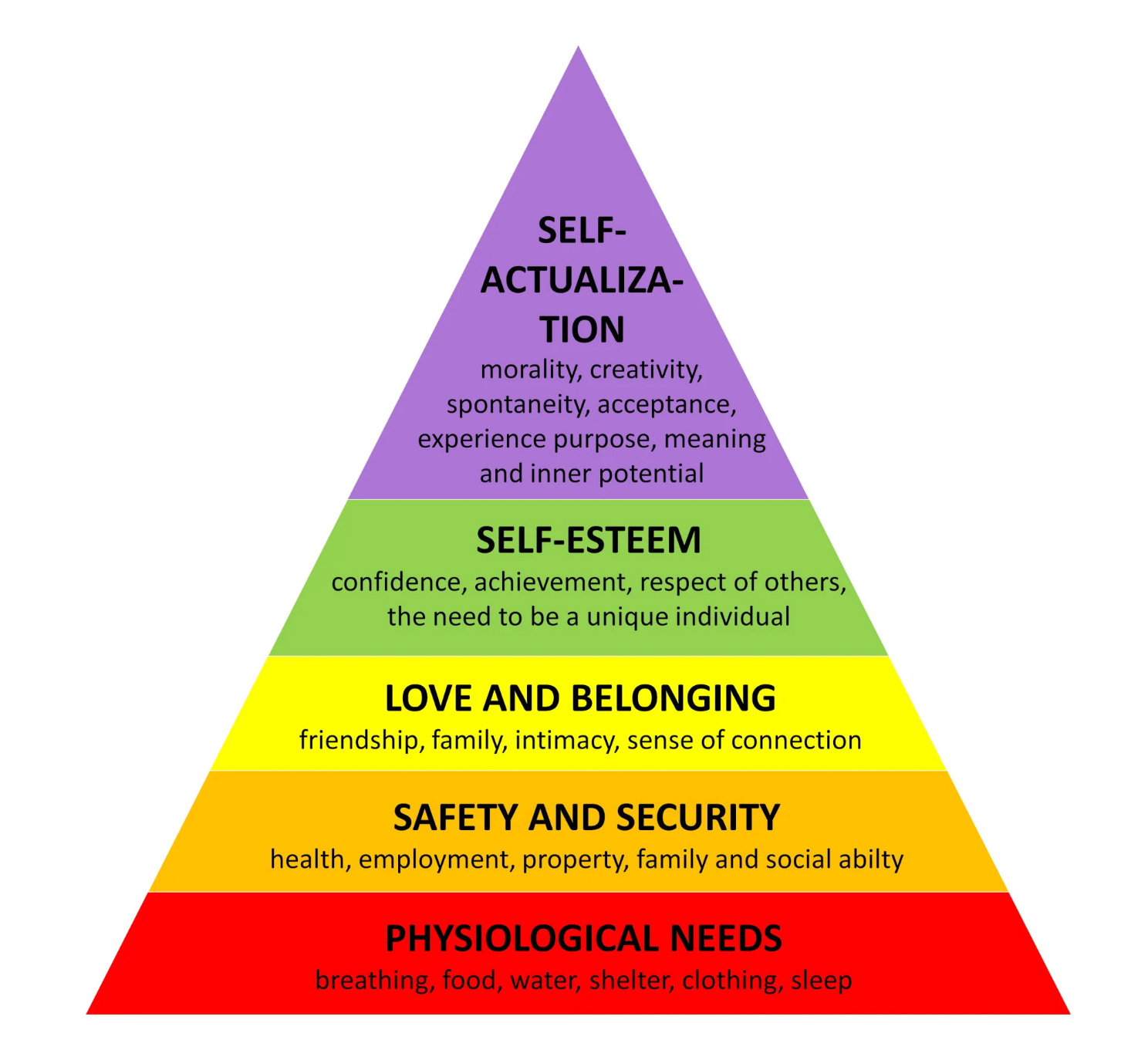

Motivational theories in philosophy often refer to conceptualizations that attempt to explain drivers of human decision and behavior. One prominent example is Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, a psychological theory represented by a five-tier model.

Maslow proposed that human needs are organized hierarchically, with basic survival needs at the base and more intellectually and emotionally oriented needs, such as self-actualization, at the top. The structure of the pyramid is intentional: Maslow believed that higher-level needs cannot be fulfilled without first satisfying foundational needs like physiological requirements, such as food, water, and shelter. Maslow argued that these are essential for survival and that one could not progress to subsequent levels without fulfilling them. Above these are safety and security. Optimal performance largely depends on maintaining the well-being and basic needs of the human body.

The next level is love and belonging, which emphasizes the importance of emotional fulfillment through relationships, whether with family, friends, or romantic partners. Following this are esteem needs, divided into two categories: self-esteem and reputational esteem.

Self-actualization is the pinnacle of the pyramid, and is more complex and subjective than the preceding levels. Maslow argues that true self-fulfillment is not attained without understanding one’s purpose and becoming the best version of oneself.

“It refers to the person’s desire for self-fulfillment, namely, to the tendency for him to become actualized in what he is potentially.

The specific form that these needs will take will of course vary greatly from person to person. In one individual it may take the form of the desire to be an ideal mother, in another it may be expressed athletically, and in still another it may be expressed in painting pictures or in inventions” (Maslow, 1943, p. 382–383).

While this overview simplifies Maslow’s theory, it highlights its core principles. Notably, self-actualization shares conceptual similarities with virtue ethics and Aristotelian Nicomachean Ethics, particularly in its focus on personal growth, purpose, and the pursuit of excellence.

3.2 Understanding Alderfer’s Theory

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs had its shortcomings and flaws. Some people criticized the lack of evidence from natural sciences, others criticized the linear hierarchical structure and subjectivity of what people define as “needs.” To address the limitations of this theory, Clayton Paul Alderfer conceptualized the ERG model, a refined version of Maslow’s hierarchy. He simplified our motivations to three categories of needs: Existence (E) relates to physical and psychological survival, Relatedness (R) addresses the need for belonging, and Growth (G) which relates to personal development and self-actualization.

Alderfer’s model differs from Maslow’s in that it is not linear, individuals can be motivated by multiple needs simultaneously. Additionally, it lacks the same hierarchical structure and acknowledges the flexibility and fluctuation of personal priorities.

Furthermore, the ERG theory includes two fundamental concepts: (i) Satisfaction-progression follows the idea that once an individual satisfies their existence needs, they will naturally progress ‘upwards’ and focus on relatedness needs, then growth needs. (ii) Frustration-regression refers to the regression of levels when higher needs are not fulfilled. Both of these concepts provide flexibility that was not previously present in Maslow’s rigid definitions.

3.3 Relation to Polygamy

You might be wondering how this relates to polygamy, but I would argue that these frameworks are deeply connected to modern women’s attitudes toward the practice. Historical polygamy has left a bitter taste in many women’s mouths, and at the very least, an overwhelming majority of them firmly oppose polygyny in their own marriages. This is a significant shift from pre-historic females who engaged in matriarchal polygamous mating habits and pre-modern women who participated in polygyny and concubinage. Where did this shift come from and what was the reason? Some would argue it is rooted in cultural evolution, suggesting that pre-modern women used cognitive dissonance reduction to make polygyny more tolerable. However, I would argue that a significant transition from prioritizing existence needs to much higher intellectual and emotional needs is largely responsible for this change.

Pre-modern women, especially within patriarchal institutions, often relied on their husbands for protection and financial provision. Since men were primary bread-winners and held economic power, women likely accepted these dynamics out of necessity, even if it conflicted with their personal desires and emotional fulfillment (frustration-regression). Even today, women who are financially dependent on their husbands are objectively more likely to tolerate various forms of abuse and cheating. Being entirely financially dependent on your partner makes it feel impossible to leave because of the risk of poverty, fear of losing support for your children (since mothers are often the primary caregivers), and cultural stigmas surrounding divorce. Contemporary women, especially in more developed nations, experience far less economic control and dependency than their historical counterparts. They are able to maintain an income independent from their spouse and pursue an education. Because of this, they are less dependent on men for their existence needs, thus allowing them to set boundaries in accordance with their values and engage in satisfaction-progression toward higher needs. Contemporary women who are seeking self-actualized, fulfilling, and conscious relationships will not partake in polygamous marriages. Such a relationship typically cannot be achieved in a polygamous dynamic, and further elaboration on this is provided in section 4.3.

Islam also acknowledges the varying needs of individuals. If a woman knows that she cannot endure such a dynamic, she has the right to leave or set conditions in her contract to protect her from such pain. The Prophet (ﷺ) demonstrated deep consideration for the emotional well-being of women, taking into account their individual needs and sensitivities. He avoided marrying women who were prone to excessive jealousy, acknowledging such a marital dynamic could be emotionally demanding and overwhelming for them.

“And among His signs is that He created for you from yourselves mates that you may find tranquillity in them, and He placed between you affection and mercy. Indeed, in that are signs for people who reflect.” [ar-Rum, 30:21]

"The women of the Ansar were very jealous. When the Prophet (ﷺ) married Zainab bint Jahsh, I said to him, 'I do not see but that your Lord hastens in pleasing you.'" Sahih Bukhari (Book 62, Hadith 158)

When asked why he did not marry a woman from the Ansar despite their beauty, the Prophet replied, “The women of the Ansar have a strong sense of jealousy and would not endure co-wives, while I am a man with multiple wives, so I would hate to do wrong to her people (the Ansar) by mistreating her.”

Overall, contemporary women are not just insolent, unruly, and disobedient. They are focusing on finding more emotional and romantic fulfillment in their relationships–something monogamy is objectively better suited to provide. As previously discussed, polygamy usually is practical for individuals seeking support, stability, and an exchange of resources. But it is not ideal for those aiming to maximize intimacy, emotional connection, and effective co-parenting within their relationships.

Section 4: The Impracticality of Modern Polygamy

4.1 Implications of Modern Polygamous Marriages

Before I delve into my subjective opinion of where I believe polygamy becomes impractical, I believe it's essential to first look at the statistics and empirical evidence regarding the effects of such [harmful] marriages in modern society.

Very few meta-analyses are conducted on the psychological effects of polygamous versus monogamous marriages. However, one prominent study by Parisa Rahmanian et al. investigated 13 other studies, all of which were thoroughly evaluated for quality and publication bias. It’s important to note these specific studies were not exclusive to Islamic nations, however I will focus on the results of traditionally Muslim societies. The psychopathological symptom severity in both groups was assessed as the primary outcome; secondary outcomes consisted of family functionality, marital satisfaction, self esteem, etc (Rahmanian et al.). Negev bedouin women in polygamous marriages psychologically suffered more than women in monogamous marriages, exhibiting higher levels of somatization, obsession compulsion, depression, anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. Jordanian first wives scored higher in all psychological symptoms, including hostility and distress severity. Palestinian and Syrian wives exhibited similar mental health issues, and Turkish women revealed higher levels of somatization disorders in senior wives. Overall, the study identified concepts such as the “First Wife Syndrome,” where the introduction of a second wife triggers an emotional crisis for the first wife, causing higher levels of psychopathological severity. Or concepts such as family strife, i.e., conflict between wives, conflict between children, conflict between son and mother, etc.

In terms of secondary outcomes, results varied. Women in polygamous marriages generally had lower family-functioning scores, no significant difference was found in marital satisfaction, and life-satisfaction and self-esteem were interestingly higher. It should be considered that things such as marital satisfaction, perception of family functionality, life-satisfaction, and self-esteem are subjective reports.

Another cross-sectional study was conducted on the psychosexual functionality of Somali women in polygamous marriages. The study noted a significant difference of psychosexual and psychological states, with women in polygamous marriages reflecting lower scores of Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI). This essentially means women in polygamous marriages exhibited decreased libido, orgasm, and general sexual dysfunction (Barut and Mohamud).

Additional subjective and ethnographic studies have investigated the impact of polygamous marriages on children, and while no significant difference has been found in childhood anxiety and depression, childhood academic performance is typically poorer. Some studies have linked polygamous marriages to higher dropout rates and less academic achievements. One study even identified how children in polygamous marriages tend to undervalue education despite being in societies and environments that prioritized education.

All of these references collectively highlight the shortcomings associated with polygamy, particularly from a familial perspective. To clarify, these studies are not representative of individual cases of polygamous marriages. While it is theoretically possible for polygamy to be practiced in a manner consistent with Islamic principles—such as maintaining fairness and justice among wives—the empirical evidence and objective observations suggest that this ideal is rarely achieved. The data displays the difficulties men often face in treating multiple wives equitably, which directly ends up having an impact on the children involved.

4.2 Inability to Maintain Justice

The Quran explicitly states that justice is a fundamental condition for polygamy. If a man cannot uphold absolute fairness in treating multiple wives, then monogamy is the preferred and more responsible choice. In contemporary times, many men struggle to maintain justice—whether emotional, financial, or in terms of time allocation—often resulting in deeply unhappy and fractured families.

It is highly unlikely that most men can achieve the same level of fairness, care, and meticulousness as the Prophet (ﷺ) did in his polygamous marriages. Before pursuing polygamy, one must seriously consider the weight of sin that may result from prioritizing personal desires over the rights and well-being of one’s wife. If you are confident in your ability to fulfill these obligations, then proceed with caution—but remember, the stakes are high, and the consequences of failure are severe.

4.3 Inherent Inequality Between the Husband and Wife

Earlier in the article, I mentioned that polygamous marriage is typically not the ideal structure for fostering a highly productive family unit or achieving a conscious, fulfilling relationship. However, I did not fully explain why—and the primary reason lies in the inherent inequality between the husband and the wife.

In Ethics, Gregg Strauss assesses various polygamous dynamics as a moral ideal, particularly in terms of equality. While I do not agree with all of his conclusions, I found his analysis of Islamic polygamous marriages compelling. I highly encourage you to read the volume yourself, as my summary is overly simplified. Strauss addresses the aforementioned shortcomings of modern polygynist marriages, such as the prevalence of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse. He similarly explores how socioeconomic pressures can unduly influence women to accept polygamous arrangements. However, he does not dismiss the possibility that polygamy can be a genuine preference for some women and that, in certain cases, they may truly benefit from it. Strauss’s primary contention with polygamy lies in its inherent structural inequality, particularly in the unequal distribution of marital commitments, which he argues is embedded in its very design (Strauss 520).

Traditional polygamy is characterized by a hub-and-spoke structure, in which there is a central spouse (typically the husband) and four peripheral spouses (typically the wives). Even traditional monogamy has its respective unequal marital commitments–which he considers to be morally objectionable–such as the wife being expected to “fully commit her time, resources, and affection to her husband” (Strauss 522). He argues that no spouse should be expected to fill the subordinate role, especially if one is demanding more than they can reciprocate. However, monogamous marriages have significantly evolved, with contemporary relationships exhibiting more egalitarian designs, striving for greater equality in moral rights and expectations. No partner is expected to sacrifice more than the other, rather, they are expected to compensate for where the other is lacking and contribute to the relationship equally (Strauss 523). Polygamy, on the other hand, has not undergone similar evolutionary modifications. Strauss argues that it is structurally impossible for traditional polygamy to achieve equality, even if resources are distributed evenly among the peripheral spouses, because the central spouse’s relationship with each peripheral spouse is inherently unequal. He illustrates this dynamic in Figure 2 of his work.

The core issue lies in the asymmetry of commitment: peripheral spouses are expected to devote themselves wholly to the central spouse, while the central spouse is only required to give a fraction of their time, resources, and emotional investment to each peripheral spouse. This hypothetical assumes he is distributing all resources and time equally amongst each peripheral spouse, yet even in this idealized scenario, the inequality persists. Strauss emphasizes that this imbalance cannot be resolved by strengthening the demands of the central spouse, as this would only create inequality amongst the peripheral spouses and, in the context of Islam, is objectively unjust. He also notes that a peripheral spouse’s consent to an unequal relationship does not render it equal; it merely reflects a subjective preference, not a structural resolution of inequality (Strauss 529).

Another significant issue Strauss highlights is the lack of control peripheral spouses have over subfamilies. In traditional polygamy, the central spouse forms subfamilies with each peripheral spouse, and while these subfamilies are interconnected, peripheral spouses “have no say in decisions by these subfamilies that may deeply affect them” (Strauss 530). This illustrates a lack of agency which further exacerbates the inequality between the husband and wife.

Strauss later proposes alternative models, such as polyfidelity, where all spouses are equally connected, but this model is irrelevant to Islamic polygamy, as it contradicts the religion’s original disposition of marital sanctions.

The purpose of this analysis is to reinforce my argument that polygamy is practical but not ideal. While it may serve certain practical purposes—such as providing stability and support in resource-scarce environments—it fails to create a maximum productive family unit or foster maximum emotional investment. The unequal distribution of time, resources, and emotional commitment between the central and peripheral spouses inherently limits the potential for an actualized, fulfilling relationship. This also further relates to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, providing additional insight into why contemporary women, who prioritize higher emotional and intellectual needs, are less inclined toward polygamous marriages.

I firmly believe that the more a husband invests in his wife—emotionally, financially, and temporally—the better equipped she will be to invest in their children. A husband should distribute all his affection, time, and resources to his wife to maximize her commitment as both a partner and a parent. This investment not only strengthens the marital bond but also enhances the sexual relationship. As evidenced by evolutionary biology, psychology, and philosophical morality, such a dynamic yields a highly actualized and emotionally fulfilling relationship.

It should be noted, however, that while polygamy is unequal on an individual scale, this does not make it inherently haram (forbidden), especially if peripheral spouses are consenting. It is merely unequal. Such a dynamic can be unproblematic if both individuals fully understand and accept the terms of their commitment, including the reduced emotional and resource investment. Some individuals may not prioritize an actualized relationship or the efficiency of their parenting; they may simply seek stability and support. In such cases, polygamy can serve practical purposes, even if it falls short of being an ideal arrangement.

4.4 Taking a Secret Second Wife

A pressing issue I have not yet addressed is the historically consistent problem of men taking additional wives without their first wife’s knowledge. While Islamic law does not require a husband to obtain his first wife’s permission for subsequent marriages to be contractually valid, this practice raises a plethora of moral and ethical concerns that should be addressed. Before delving into these issues, however, I want to clarify that such behavior is neither ideal nor entirely permissible in Islam. The only known instance in which the Prophet Muhammad (ﷺ) married another wife without informing his existing wives was under extraordinary circumstances—specifically, his marriage to Saffiyyah during a time of war, when he was virtually unable to communicate with his other wives. Even in this case, once he returned, he immediately informed them of his marriage to Saffiyyah. There is no documentation of the Prophet (ﷺ) deliberately hiding a wife from his other spouses. As Muslims, we are expected to emulate the Prophet’s (ﷺ) values and behaviors, and secrecy in marriage directly contradicts values consistent with his character, such as transparency and honesty.

Taking a second wife in secret introduces a range of moral and practical issues. I will outline the most significant concerns, beginning with sexual health risks: Engaging in sexual relations with multiple partners without their knowledge poses serious health risks. All parties involved have the right to be informed so they can make decisions about their safety, including the use of protective measures to prevent sexually transmitted infections (STIs) or diseases (STDs). STIs are incredibly common, and in rare cases, they can even be transmitted without direct sexual contact. By withholding this information, a husband not only endangers his wives’ health but also his own, creating a cycle of potential harm.

A second caveat is emotional betrayal. Many women are uncomfortable with non-monogamy for various reasons, and withholding information about a second marriage can cause profound emotional harm. The Prophet (ﷺ) himself avoided marrying women who were prone to jealousy, recognizing the emotional toll such dynamics could take. Secrecy in marriage constitutes a betrayal of trust, which can lead to long-term psychological distress (including disruption of neural pathways) for the first wife and damage the marital relationship irreparably.

Third is the issue of fundamentally violating the wife’s right to seek divorce if she deems the circumstances unjust or intolerable. Islam was the first major religion to explicitly grant women the right to initiate divorce—a groundbreaking ruling at the time—ensuring that they were not bound to marriages where their rights were neglected or where they suffered harm. Men who take secret second wives often do so precisely because they likely know she would choose to leave if she were aware. By concealing a second wife, a man strips his first wife of this God-given right, forcing her into a marriage dynamic she did not consent to and may not accept had she known the full truth. Such deception is not only inconsistent with the values of Islam, it forces the wife into a position where she is unknowingly subjected to a dynamic that she has every right–both religiously and ethically–to reject.

The fourth, and arguably most pressing, caveat is the issue of dishonesty and deception. Some argue that lying is permissible in certain situations, but in this case, deception is indefensible. The lie will inevitably come to light—either during the husband’s lifetime or after his death—causing even greater emotional distress for the wife and any children involved. This is not a harmless omission; it is a deliberate act of dishonesty that undermines the foundation of trust in a marriage. Furthermore, such secrecy produces complications with inheritance. If a husband does not legally register his marriages or disclose them to his family, the distribution of wealth to his children and spouses cannot be properly managed. This effectively withholds rightful inheritance from his wives and children, prioritizing his own selfish desires over their financial and emotional well-being.

The fifth caveat, informed consent, serves as an extension to the issue of dishonesty. Considering all potential issues outlined above, maintaining informed consent is a volatile constituent of an ethical relationship. Consent is not considered informed if one party is deceived, manipulated, coerced, under the age of consent, under the influence of drugs or alcohol, unconscious, or subject to a power imbalance. This is specifically because of the possibility that the individual otherwise would not consent to sexual intercourse if they were informed. This proposes a moral gray area, especially in the case of sexual health where you may unknowingly or knowingly transmit a disease. By hiding a second marriage, a husband violates his first wife’s right to make informed decisions about her health and well-being. In many legal jurisdictions, this may fall under criminal offenses such as fraudulent inducement of sex, criminal transmission of an STI, and intentional or reckless harm. Intentionally misleading someone violates informed consent, even in regards to sexual health risks. In some cases, it can potentially qualify as sexual assault. Even Saudi Arabia has implemented legal frameworks mandating the disclosure of STIs to spouses and requiring patients to take measures to prevent transmission.

Considering all of this information, it is reasonable to conclude that by making such a decision, it is highly likely one will inevitably fall into secondary acts of sin. It introduces a cascade of moral and practical problems that cannot be justified. From sexual health risks and emotional betrayal to dishonesty and inheritance complications, the harms far outweigh any perceived benefits. While there may be rare and extraordinary exceptions, such as the Prophet’s (ﷺ) marriage to Saffiyyah, these do not provide a blanket justification for secrecy in marriage. As Muslims, we are called to emulate the Prophet’s (ﷺ) example of transparency, honesty, and respect for our spouses. Secret marriages not only violate these principles, but also undermine the trust and integrity that are essential to a healthy marital relationship. In an overwhelming majority of cases, such behavior is not only impractical but deeply immoral and unethical.

Section 5: When Polygamy is Practical and Beautiful

It is essential to maintain a balanced perspective, which includes acknowledging both the challenges and potential benefits of polygamous dynamics. While polygamy is often impractical in modern society due to various injustices and ethical concerns, its original purpose in Islam was deeply rooted in compassion, social responsibility, and care. There are circumstances in which polygamy serves a practical function, and in certain cases, it may even be ideal—provided it is approached with sincerity, fairness, and a commitment to justice. When practiced correctly, polygamy can be a source of immense reward and goodness, providing an environment in which a marriage thrives.

One of the most significant benefits of polygamy is its ability to provide financial and emotional security for women in need. In societies affected by war, economic instability, or gender imbalances, polygamy can function as a social safety net, offering stability to widows, divorcees, and other vulnerable women who might otherwise struggle to secure financial or social support. Even historically, polygamy has also facilitated the expansion of strong, united families. Although, I would argue that prioritizing quality over quantity in familial relationships is more beneficial.

However, polygamy should only be pursued when all parties involved are informed and consenting. Rather than attempting to impose this structure on women who are opposed to it, men should seek partners who willingly accept such an arrangement. In the case of the Prophet’s (ﷺ) marriage to Saffiyah, this was not arbitrary or disruptive to his other wives, as they were already part of a polygamous marriage and consenting. As mentioned in section 2, the Prophet (ﷺ) himself was mindful of a woman’s jealousy and emotional tolerance for polygamy, avoiding marriages that would place undue distress on his wives. It is crucial that all individuals involved carefully consider the implications of engaging in a polygamous dynamic and acknowledge the potential sacrifices it may entail.

Polygamy is particularly rewarding when practiced with pure intentions and not driven by predatory desires. For instance, choosing to marry a young, inexperienced woman over a widow or divorcee in need of support, despite the latter carrying greater reward, is a reflection of misplaced priorities. While marrying for sexual gratification is not inherently haram, men should remain mindful of the emotional impact such motivations may have on their existing wives. Sexual discipline is an important virtue. If a man desires to marry solely for this reason, he should reflect on his perception of women, ensuring he is not reducing his wives to mere outlets for sexual release. A wife, in the Islamic framework, is a source of goodness and reward, not simply a means to satisfy carnal desires.

Another frequently debated scenario is whether a man should take a second wife if his first wife is unable to conceive. While this is permissible in Islam, it is a decision that must be approached with profound sensitivity. If a woman has dedicated her life to her husband and built a strong emotional bond with him, the prospect of seeing him start a family with another woman can be deeply painful. If she lacks strong emotional attachment, perhaps such an arrangement may not be distressing; however, if she is deeply invested in the relationship, her feelings must be considered with the utmost care. Personally, I would not choose to leave my husband if he were infertile, as my commitment to him is rooted in love, not merely the prospect of bearing children. Thus, I am capable of finding contentment in life with him alone. I trust that Allah’s decree is just, and if parenthood is not written for us in this life, it may be granted in the hereafter. A man who truly loves his wife would prioritize their shared bond over external desires, rather than subjecting her to such pain. Islam emphasizes patience and submission to what is divinely ordained, and true love, in my view, is reflected in unwavering devotion despite life’s challenges. That being said, if a woman consents to her husband taking another wife under such circumstances and it does not cause her harm, then there is no inherent issue. However, such matters should always be discussed in advance rather than being decided unilaterally after marriage. Transparency, honesty, and mutual understanding are essential to ensuring that polygamous relationships are ethical and conducted with integrity and fairness.

Section 6: Conclusion

Polygamy is a complex institution; it is neither inherently good or inherently bad. Its execution and intent dictate whether it uplifts and safeguards the women involved, or ruins them. The assertion that ‘polygamy is practical, not ideal’ is a prescriptive argument, while the evidence presented throughout this article—rooted in evolutionary biology, neuroscience, history, psychology, and philosophy—constructs the foundation of my descriptive argumentation. These function in conjunction to convey the nuance of contemporary polygamy, rather than positioning it into a binary of ‘good’ or ‘bad’. Despite its misuses, there is divine wisdom in its practices. There is no universal decree that polygamy or monogamy is the definitive path; rather, the choice hinges on individual priorities, emotional capacity, and the pursuit of self-actualization. Above all, it demands an unwavering commitment to justice.

For those who seek deep emotional investment, unwavering companionship, and an enduring love that fosters personal growth, monogamy remains the superior and ideal choice. It offers the sanctity of devotion, the assurance of integrity, and the beauty of two souls progressing toward a better self. It establishes a home where love is singular and undivided, providing children with a stable, intimate representation of partnership and familial unity. Yet, for others, polygamy may serve a different, yet equally valid, practical function. It may provide security, financial stability, and a sense of duty beyond the realm of romance.

However, the sanctity of Islamic polygamy has been tarnished by those who misuse it, reducing it to a vessel for unchecked desires rather than a structure of care and responsibility. These distortions create a sexual differential, one that normalizes the subjugation of women under the guise of religious zealousness. Such perversions of polygamy must be dismantled. It is my sole reason for writing this. For years, I have had my faith tested by the sickening lies and sentiments of misogynists who twist the religion. I have held the scripture in my hands and watched it crumble like burnt paper. The silt of it filled my throat and formed a lump that prevented me from swallowing the beauty of scripture without pain. It took me a long time to be able to read those words without feeling confused and overwhelmed. I only seek to help other women be able to consume religion without pain, and hold the sins of men under a light so that they may reflect. Islam is just, and it does not allow for the subjugation of women. Because of this, immoral men lie, they deceive, and they distort the religion to fit their desires. They hinge on semantics and obscurities in order to force their way. The least I can do is bring ease and clarity to some hearts, and remind them that this is not the religion.

So thus, I conclude that polygamy is practical, not ideal. It is a structure that can function under the right conditions but rarely achieves the emotional and spiritual fulfillment that monogamy so effortlessly provides. The highest forms of love and partnership are built on reciprocity, devotion, and undivided attention—ideals that monogamy is uniquely designed to uphold. And so, while polygamy may be permissible, monogamy remains the pinnacle of love’s truest expression, where hearts are bound not by duty, but by an unyielding and singular affection.

Qualifications: Computer Science (AI & ML specialization) and Biological Science (Neurobiology specialization)

Alger, Sarah J., et al. “Complex patterns of dopamine-related gene expression in the ventral tegmental area of male zebra finches relate to dyadic interactions with long-term female partners.” vol. 19, 2, 2020. Genes, Brain, and Behavior, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gbb.12619.

Barut, Adil, and Samira A. Mohamud. “The psychosexual and psychosocial impacts of polygamous marriages: a cross-sectional study among Somali women.” BMC Women's Health, 2023, https://bmcwomenshealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12905-023-02830-1.

Carter, C. S., et al. “Oxytocin and Vasopressin in Mammalian Reproduction and Behavior.” Biological Psychology, vol. 31(3), 1992, pp. 133-158.

Dixson, A. F. “Sexual behavior, sexual swelling, and penile evolution in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes).” Spring Nature, June 1994, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF01541563.

Eberhard, William G. Sexual Selection and Animal Genitalia. Harvard University Press, 1985. Degruyter.

Garrison, Jennifer L., et al. “Oxytocin/Vasopressin-Related Peptides Have an Ancient Role in Reproductive Behavior.” Science, 26 October 2012, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3597094/. Accessed 29 January 2025.

Maslow, Abraham. A Theory of Human Motivation. vol. 50(4), Psychological Review, 1943.

Miller, Geoffrey. The Mating Mind. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2001.

Rahmanian, Parisa, et al. “Prevalence of mental health problems in women in polygamous versus monogamous marriages: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Archive Womens Mental Health, vol. 24, 2021, pp. 339–351. Springer Nature Link, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00737-020-01070-8?utm_source=chatgpt.com#citeas.

Strauss, Greg. “Is Polygamy Inherently Unequal?” vol. 122, no. 3, 2012, pp. 516-544. The University of Chicago Press, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/664754.

Walum, Hasse, et al. “Genetic Variation in the Vasopressin Receptor 1a Gene (AVPR1A) Associates with Pair-Bonding Behavior in Humans.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 105, no. 37, 2008, pp. 14153–14156. PNAS, doi:10.1073/pnas.0803081105.

Young, L. J. The Neurobiology of Social Bonding: Implications for Understanding Anxiety, Depression, and Attachment. no. 50(11), pp. 773-784.

Hi raz,

This was such a great first article! I love how well you put your thoughts together, it flows so smoothly, and your vocabulary is really impressive. I’m curious, how did you develop such a strong writing style? Any favorite resources or tips for improving vocabulary and clarity? Honestly, I want to grow and be like you, you’re my role model.🥰

Looking forward to reading more from you🤗💕

I wanted to take a moment to share how deeply your article on polygamy resonated with me. Your words were not only enlightening but also profoundly compassionate, offering a perspective that is so often misunderstood. In fact, I was so moved by your piece that I want to print it out.

You articulated the Islamic view of polygamy with remarkable clarity, particularly the emphasis on it being a necessity rather than a lifestyle, a principle our Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, embodied through his actions during times of war, orphaned families, and societal imbalance. This distinction is crucial, and I recently found myself explaining this very nuance to my non-Muslim friends. Many had conflated polygamy with indulgence, but your article gave me the framework to clarify that it’s rooted in compassion, justice, and responsibility toward vulnerable members of the community.

Beyond the content itself, your writing style is exceptional. The way you weave historical context, Islamic ethics, and modern relevance together is amazing. You have a gift for making complex ideas feel approachable.

Thank you for sharing your voice and knowledge with the world. Articles like yours not only deepen understanding but also remind us of the beauty in Islam’s balanced teachings. Please keep writing! your words matter more than you know.